Spiritism: A Comprehensive Analysis for Understanding and Reflection

Spiritism, also known as the Spiritist doctrine or Kardecism, is a body of knowledge that seeks to provide a deep understanding of life, death, and the purpose of existence. Established in France during the mid-19th century by Allan Kardec (the pseudonym of Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail), this doctrine defines itself as being “based on the existence, manifestations, and teachings of spirits.” Far from being a mere belief system, Spiritism presents a threefold nature—philosophical, scientific, and religious—aimed at explaining the spirit’s return to material life and its continual evolution.

I. Unveiling Spiritism

Definition and Nature: A Doctrine with a Threefold Aspect

Spiritism is a spiritualist and reincarnationist doctrine that seeks to unravel the mysteries of life and the universe through communication with spirits. Allan Kardec, the codifier, developed this doctrine based on a set of principles designed to improve human understanding of its own nature and destiny.

Spiritism stands out for its multifaceted approach—simultaneously philosophical, scientific, and religious:

- Philosophically, Spiritism interprets life by engaging existential questions such as the origin of the soul, the purpose of earthly existence, the destiny after death, and the nature of pain and suffering.

- Scientifically, it focuses on the study of mediumistic phenomena caused by spirits, which are seen as natural—not supernatural—and capable of rational investigation. Kardec began his inquiry by observing the “spinning table” phenomena, seeking a reasonable explanation for their seemingly intelligent movements.

- Religiously, Spiritism aims primarily at the moral transformation of the individual. It seeks to revive the teachings of Jesus Christ in their purest form—simplicity, love, and charity—without relying on external rituals, formal clergy, or ceremonial practices.

This threefold aspect reflects the strategy behind the formation of the doctrine. In the 19th century, positivism and scientific rationalism often clashed with religious dogmas. By calling Spiritism philosophical, Kardec offered a rational structure; by claiming it scientific, he granted it legitimacy; by retaining the religious dimension, he satisfied the spiritual needs of humanity. As such, Spiritism sought to become a “rational faith” or a “science of the spirit.”

Origins and the Role of Allan Kardec in the 19th Century

Spiritism was born in France in 1857 with the publication of The Spirits’ Book (Le Livre des Esprits). Its genesis is closely tied to the famous “spinning table” gatherings, where tables seemed to move and respond intelligently. Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail (Allan Kardec) was a pedagogue who investigated these manifestations systematically. He concluded that the responses came from spirits—souls who had survived physical death.

In 1858, Kardec founded the Parisian Society for Spiritist Studies (SPEE), which played a critical role in consolidating, testing, and organizing the doctrine’s teachings. Spiritism emerged during a time of great social, political, and intellectual transformation in Europe, shaped by Enlightenment ideas and the Industrial Revolution. Kardec’s pedagogical discipline contributed to a rigorous approach, aiming not for sensationalism, but for an intellectual framework that positioned Spiritism as a “science of the spirit.”

II. Foundations of the Spiritist Doctrine

Belief in God and Immortality of the Soul

Spiritism is grounded in faith in a single God, the supreme intelligence and primary cause of all. The soul, or spirit, is immortal and uses the physical body as a temporary vessel. Created imperfect, spirits evolve throughout multiple incarnations in pursuit of intellectual and moral progress—emphasizing personal responsibility rather than divine predestination.

Reincarnation: The Path of Spiritual Evolution

Reincarnation is one of Spiritism’s most distinctive tenets. Spirits return to physical life repeatedly to learn, improve, and repair past mistakes. Reincarnation is viewed not as punishment but as a loving mechanism of justice and learning, explaining inequality and suffering as consequences of past choices.

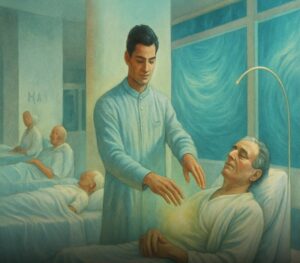

Communication with Spirits and Mediumship

Communication with the spirits—mediated by individuals known as mediums—is a cornerstone of the doctrine. Mediumistic ability varies and includes physical effects, psychography (automatic writing), or psychophony (speaking through a medium). Spiritism encourages responsible, charitable use of mediumship as a tool for knowledge, healing, and spiritual progress.

Plurality of Existences and Inhabited Worlds

Spiritism teaches that life is not limited to Earth. The universe contains countless inhabited worlds at different evolutionary levels. Spirits may reincarnate in other worlds to gain diverse experiences and continue progressing—reinforcing a sense of universal fraternity.

Law of Cause and Effect (Karma) and the Perispirit

Every action produces consequences that return to the spirit, either in this life or future ones. Good deeds create harmony; negative actions generate future challenges. The perispirit—a semi-material envelope between the soul and the body—records these impressions and carries them across lifetimes, ensuring continuity and justice.

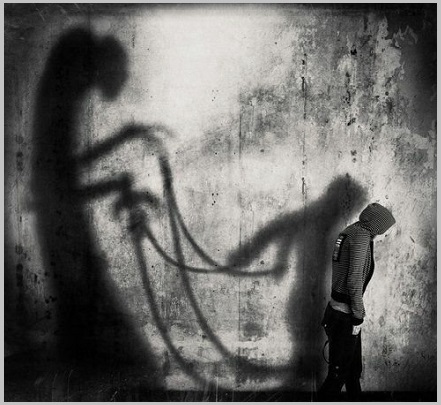

The Phenomenon of Obsession

Spiritism explains obsession as the harmful influence of a discarnate spirit over a living person, affecting thoughts, emotions, or actions. Treatment involves moral reform, prayer, study, and charitable acts to rebalance vibrations and break spiritual ties of negativity.

III. Practices and Social Aspects of Spiritism

Absence of Rituals and Clergy

Spiritism rejects ritualistic practices, altars, talismans, sacraments, or formal priesthoods. Worship is internal, guided by the principle “God must be adored in spirit and in truth.” All services are free of charge, emphasizing charity, reason, and simplicity.

Spiritist Meetings and Study Groups

The Brazilian Spiritist Federation promotes structured activities such as doctrinal study meetings, systematic courses (ESDE/EADE), and serious mediumistic sessions restricted to trained workers. Continuous study and moral improvement are core Spiritist practices.

IV. Spiritism in Society

Spiritism teaches that social inequality results from human selfishness—not divine will. Wealth and poverty are seen as tests chosen by the spirit before birth. Ethical transformation arises through charity, humility, and altruism. In Brazil, Spiritism flourished by blending intellectual and popular elements, despite early Catholic opposition. Over time, it influenced culture deeply and even intersected with other spiritual traditions like Umbanda.

V. Debates and Perspectives

Spiritism claims to bridge science and spirituality, but many scientists challenge its methodology. The doctrine coexists with an openness to questioning and internal debates—for example, over modern spiritist works and interpretations. Spiritism respects all religions, encouraging harmony and dialogue rather than proselytism.

VI. Conclusion

Spiritism offers a broad philosophical and spiritual worldview rooted in rational faith. Its pillars point to life as a journey of continuous learning and moral elevation. By emphasizing free will, responsibility, and charity, it invites individuals to reflect, transform, and evolve spiritually across time and space.

Share this content:

Post Comment